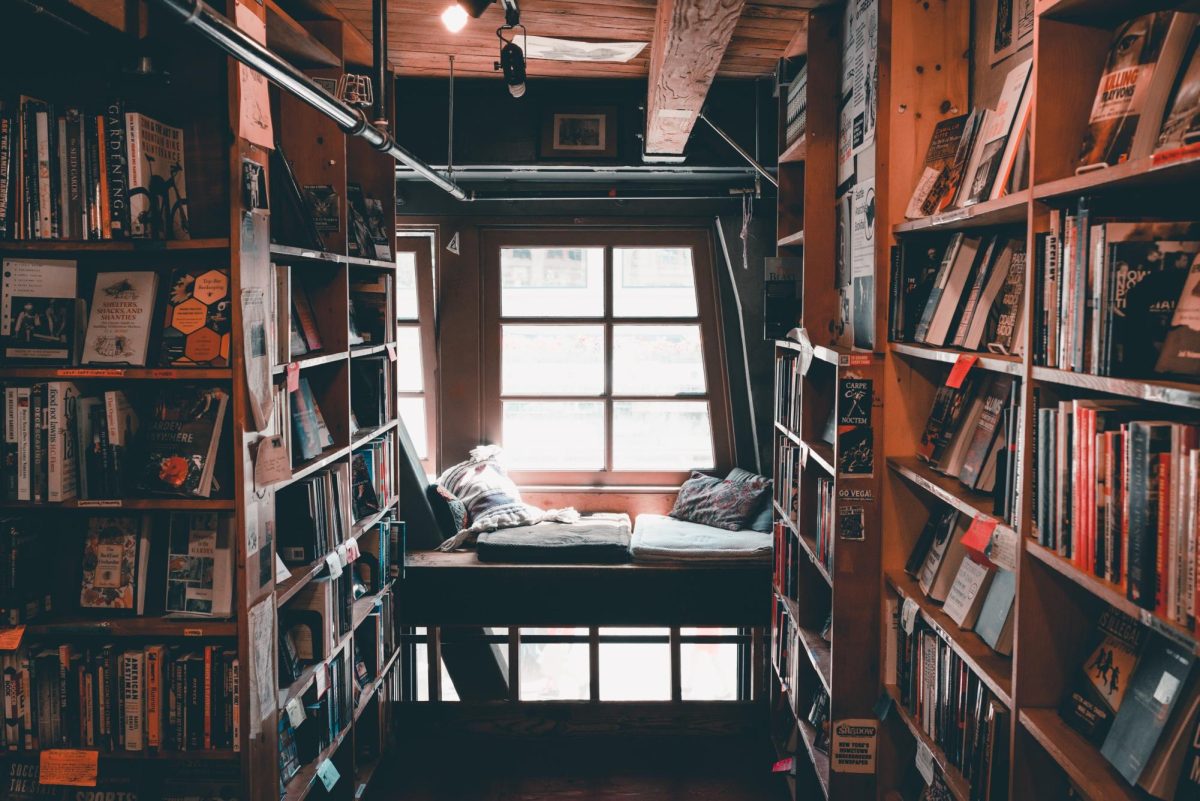

On Sept. 21, the Bucks community was asked to consider how we teach our children to read, with the showing of a documentary entitled “The Right to Read” and a panel discussion thereafter in the Zlock Performing Arts Center on the Newtown campus.

The documentary followed Kareem Weaver—a National Association for the Advancement of Colored People activist and veteran of the Oakland, California school district—as he petitioned the district to change the curriculum it uses to teach children literacy.

The discussion panel comprised Dr. Brooks Imel, an education consultant who works with neurodiverse students; Kevin E. Leven, an opinion columnist for the Bucks County Beacon; and Lynne B. Millard, the principal leadership coach and special advisor of school impact at the School District of Philadelphia.

“If you can’t read, you can’t access anything in our society. Imagine you’re in the Stone Age, and you don’t have any stone. Imagine you’re in the Bronze Age, but you don’t have any bronze. We’re in the Information Age. Without reading, you can’t get any information,” Weaver said in the film.

The film discusses a 1970s-era academic debate with modern ramifications called “The Reading Wars,” in which two opposing factions promoted a different method of reading instruction.

One side advocated for a “whole language” approach in which students are taught whole words and sentences from the start, whereas the other advocated a phonetic approach in which words are first broken down into their component sounds.

The film and panel members argued mostly for the phonetic approach. Both, however, were quick to stress that in many districts, the whole language method pervades.

“It’s really strange that the Reading Wars are still going on. In academia, this is not debated. Only in policy is the debate alive,” Imel said.

“This is just another example of us ignoring evidence-based science at our own peril. You see this also with climate change policy,” said Leven.

The documentary emphasized throughout that teachers are forced by the district to teach using apparently ineffective whole language curriculum whose inefficiency was demonstrated with several examples.

One such example showed an exercise prescribed by many curriculums in which a teacher shows students a sentence, one word of which is covered. Students are then asked to call out the covered word—guessing.

Another example shown came in the form of a home recording of a child completing school work on a laptop.

On the screen is an illustration of a girl painting a door purple with a paintbrush. Underneath appears the sentence, “She paints the door purple.”

When asked, the child reads the sentence with ease. But when the parent covers the illustration above the sentence, “She paints the swing purple,” the child babbles and is therefore not reading at all, merely looking at the picture and guessing.

The film and panel also emphasized how this issue is radicalized, describing an “illiteracy pipeline” and invoking antebellum slave codes in which punishments were levied on anyone who taught a Black person—free or enslaved—to read.

“This problem we are now dealing with is built on malintent. We are still recovering from that. There is a system of the haves and the have-nots,” Millard said.

During the panel discussion, Imel described the method of teaching literacy that he said to be consensus in academia. “You teach it in stages. The first is phonemic awareness, which is getting students to be aware of the sounds that make up words. The next stage is where students learn to associate these symbols, letters, with the sounds. This actually hijacks the brain’s facial recognition circuitry,” he said.

The film depicted several Black families over several years as they nurtured their children into educated readers, noting the value of talking to babies and toddlers even when they can only respond with babbling.

Throughout the documentary, Weaver showed enmity toward the curriculum sold by a company called Lucy Calkins, which used the whole language approach.

By the end of the film, much of Weaver’s petition had been granted and Lucy Calkins had changed their methods yet admitted no wrongdoing.

“It’s very difficult to stop something that is so profitable. But if your curriculum is used nationwide, it’ll be profitable if it’s good, too,” said Leven.