With the numbers growing rapidly by the day, the novel coronavirus that first struck in January has affected over three million people across 185 countries to date. As the global death toll climbs to numbers over 200,000, many are left wondering if there is an end in sight.

To combat the spread of the virus in the U.S., state governors began catching on to the trend of implementing “stay at home” orders throughout the last week of March. These measures included shutting down all non-essential businesses, urging Americans to stay in their homes and to practice “social distancing” if they had to go out in public. All states, including the territory of Puerto Rico, have executed the regulation except for the midwestern states of Nebraska, North and South Dakota, Iowa and Arkansas.

The orders have forced at least 316 million Americans to stay in their homes until further notice. Over 40 days later, protests have been popping up across the country, defying social distancing recommendations, as masses demand their states to reopen. Protesters state the poor condition of the economy and its potential worsening if orders are extended, as reasoning for the demonstrations.

While the protesters’ concerns are valid to a certain degree, their actions are putting themselves and thousands, if not millions, of other people at serious risk. On that note, many of the participants in the crowds are among the part of the population that still believe the virus to be a hoax.

However, were these protesters to enter a hospital to see conditions for themselves, they may decide to stay back in their homes. In the places where social distancing is impossible, where you must come within inches of a virus infecting millions to continue to do your job, the idea of staying home from work doesn’t sound that bad. This is the new normal for the population in the medical field that has been thrust into the thick of combatting COVID-19.

To use the word “blindsided” even sounds like putting it lightly. Healthcare workers have faced a myriad of unprecedented challenges and changes within their professions in a very short time frame. From overcrowded hospitals and clinics teeming with exposure to an extreme worldwide scarcity of vital personal protective equipment (PPE), workers in the medical field are struggling to keep their heads above water.

Rebecca McCool, a medical social worker from Churchville, works at the Einstein Medical Center of Philadelphia. She sees about 80 COVID-19 patients per day. Running their charts to check for test results and worsening symptoms are among some of her daily duties. McCool shared that Einstein has had to reallocate what were previously shared-patient rooms to now single-patient rooms to house the contagious COVID-19 patients. When it comes to protecting themselves, Einstein workers have had to make do with what they have: reusing surgical masks, sterilizing and reusing N95 masks, surgical gowns, and face shields. McCool, who was away from work when everything was first beginning, remembers coming back to see her new work conditions, “walking into work felt very eerie. There are no visitors, no outpatient procedures which means fewer patients walking to appointments. The hospital is just very quiet. When I walked to my office, I realized this was going to be a very different work life for me.”

McCool was able to give some insight into the testing and treatment processes too. “We are fortunate at Einstein because we have the ability to get the results in about eight hours compared to other places where the test takes up to 72 hours,” McCool explains. The test consists of a deep, often uncomfortable 30-second nasal swab of the throat. As far as treatment goes, “we use oxygen which usually most of the patients require a high amount of. We use ventilators for more serious cases. I have also seen hydroxychloroquine used. For non-severe cases, we will send them home to self-isolate at home or at their skilled nursing facility.” Therein lies some of McCool’s hardest challenges.

Finding places for these patients to go, like shelters or nursing facilities, is proving to be almost impossible. Most facilities are already full of positive cases or are not taking new patients in order to protect their current residents and staff. Some patients that require self-isolation in their home do not have the luxury of self-isolating, and “we are having a hard time finding Covid shelters because they just are not up and running or they are full,” says McCool.

Another local medical professional, Margaret Hamel-Daymon MSN, RN, CRNP of Chalfont, was also willing to talk about her experiences at work. As a pediatric nurse practitioner, Hamel-Daymon is the team lead of sedation/radiology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and has been serving in her field for over 25 years. A typical day for her as of recently includes: “sedating urgent cases (mostly oncology patients for MRIs and/or lumbar punctures and bone marrow aspirates) and triaging or rescheduling patients deemed non-urgent until after COVID-19 crisis improves.” CHOP, like many other medical facilities, has been subject to an influx of patients, and Hamel-Daymon describes how her workload has changed: “typically we sedate 10-15 patients per week. With the COVID-19 crisis, we sedate one to five per day.”

Due to the high rates of contagiousness, many patients suffering from the coronavirus must do so on their own. At CHOP, only one parent/caregiver can accompany the child; but for most positive-tested adults at hospitals such as Einstein, visitors are prohibited, and family must rely on the medical staff for information about loved ones. As far as the demographics of the virus go, it has had the worst effect on the elderly and those with comorbidities. “Thankfully, children seem to exhibit milder symptoms than adults,” reports Hamel-Daymon.

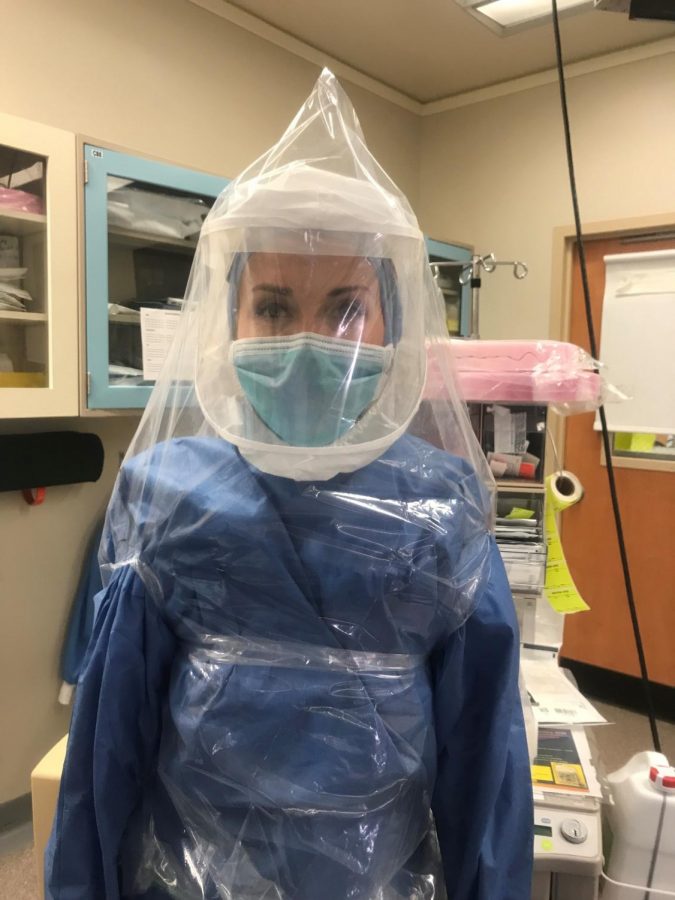

One Ivyland resident that preferred to remain anonymous works as a Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist at a level one trauma center in a local hospital. While they have not run out of PPE, they have been reusing as much equipment as possible. “Many of my colleagues spent money on safety equipment on our own; safety goggles, pulse oximeter, phone soap. Many of us bought our own PAPRs which cost about $1200.” The staff was able to use continuing education to purchase protective equipment. PAPR stands for powered air-purifying respirator and is essentially a battery-powered full coverage face shield/helmet that filters contaminants out of the air that flows inside.

These are just a few accounts of what hundreds of thousands of medical professionals are facing each day. Hamel-Daymon offered some lasting advice to the public, emphasizing that “people need to understand that this is not like the flu. It is much more virulent. Social isolation will help to flatten the curve… For those that believe it is their right to go out… they do not have the right to infect others.” As states begin to reopen and people convince themselves the worst is behind us, threats still loom in the future. It is important to be patient, continue to listen to medical professionals, and take this seriously. It is in the hands of the public to lighten the heavy load weighing down the medical community and put an end to this rampant virus.