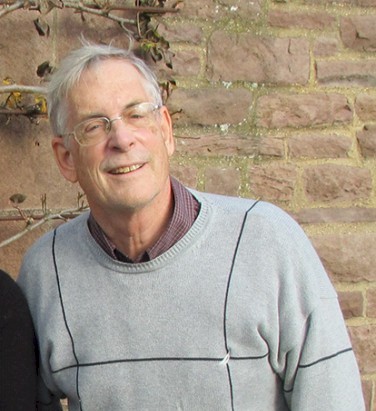

Dr. Christopher Bursk, a professor for nearly 50 years at Bucks County Community College who was also a student, mentor, poet, activist, humanitarian, friend, husband and father, passed away on June 21. He was 78 years old.

Bursk inspired many people.

“Think of Robin Williams in Dead Poets’ Society—but for real,” said Professor Ethel Rackin, a professor at Bucks, the director of Bucks County Poet Laureate program and author of three poetry books.

He was a man who seemed to have it done it all.

Bursk was no ordinary professor. He went above and beyond for his students.

Bernadette McBride, an instructor at Bucks, a close friend of Bursk, and author of four full-length poetry collections, remembers her first interaction with him.

McBride met him in the 1990s at a poetry reading. She didn’t know anyone, but Bursk came right up, invited her to read, and drew her in to the poetry community.

“I keep envisioning the rumble and sight of him, hair askew, pushing down the hallway toward his office, bent to a loaded-down cart of books and student handouts,” she recalled.

Bursk did a lot for his students in making them feel welcome.

Greg Probst, a former student of Bursk’s, had been struggling with the death of his mother. He asked to complete an independent study with Bursk, and he agreed.

Bursk convinced Probst to pursue a career in teaching. Probst just finished his first year of teaching, and he loves it. Probst said he would never have discovered his love for teaching if it wasn’t for Bursk and his dedication to his job.

Bursk received his BA from Tufts University in 1965; his PhD from Boston University in 1975; and his MFA from Warren Wilson College in 1988.

But to really experience what his students went through, Bursk became a student again at Bucks to earn an Associate’s Degree.

“This unusual choice is an example of the way in which this extraordinary man truly cared about the lives of others. He tried his best to walk in others’ shoes so that he could be of service,” Rackin said.

Bursk earned his AA in English with Honors and Latin Honors with the Class of 2021.

Bursk still found time to publish 18 books of poetry.

His work has been recognized by the AWP Donald Hall Poetry Prize, the Allen Ginsberg Prize, the Green Rose Prize, the Patterson Prize, Bellingham Review’s 49th Parallel Awards, the New Letters Prize in Poetry, and Milt Kessler Book Award.

He also won the 1978 Bucks County Poet Laureate and was a recipient of the PEW, NEA, and Guggenheim fellowship.

He shared his love of poetry with the community.

He held a spring poetry workshop that had started out as just a handful of poets meeting at Bucks’ Fireside Lounge.

The group quickly grew, and they met weekly for almost 40 years.

McBride said most members of this community still keep in touch to this day and many have become award-winning, published authors.

“He tapped people’s thinking skills, stretched their imaginations, gave himself wholeheartedly to others with no expectation of reciprocity,” McBride explained.

But Bursk was more than a great professor, a great mentor, and a poet. He was an activist and a humanitarian as well.

He spent 30 years teaching at the Bucks County Prison, and he donated a lot of his time to food banks and women’s shelters.

Professor emeritus Steve O’Neill, a longtime friend of Bursk’s, said “He’s always been involved, engaged, and committed to good causes.”

He recalled the days when he and Bursk were picketing for better working conditions for grape workers in California.

“It’s safe to say that some members of our community wouldn’t be alive, wouldn’t be sober, wouldn’t be writing, wouldn’t be on their chosen life-path, would have given up long ago, if it weren’t for Dr. Christopher Bursk,” Rackin explained.

Bursk also had an eccentric side. O’Neill fondly remembers Bursk’s office that was so cluttered with papers, stuffed animals, and bats and shoes that the fire department told him it was becoming a fire hazard.

Bursk will be remembered “for his supernatural being,” his ability to seemingly do everything, Rackin said.

He will be remembered for the lives he made better at the women’s shelter and at the prison.

He will be remembered by his students for the adventures he took them on. McBride remembered one day seeing Bursk climb out of a first story window, his students in tow.

“His most important ‘work,’” McBride said, “is inherent in all [he did]. It’s that which makes all good possible: He evinced authentic love.”